Nova Scotia Archives

Archibald MacMechan

Halifax Disaster Record Office Materials

"Journal", clippings

12 April 1918. — 3 pages : 30 x 39 cm.

note: transcription publicly contributed - please contact us with comments, errors or omisions

HALIFAX DISASTER RECORD OFFICE

ARCHIBALD MACMECHAN, F.R.S.C.

DIRECTOR

HALIFAX, N.S.

April 12, 1918.

JOURNAL

[Newspaper clipping]

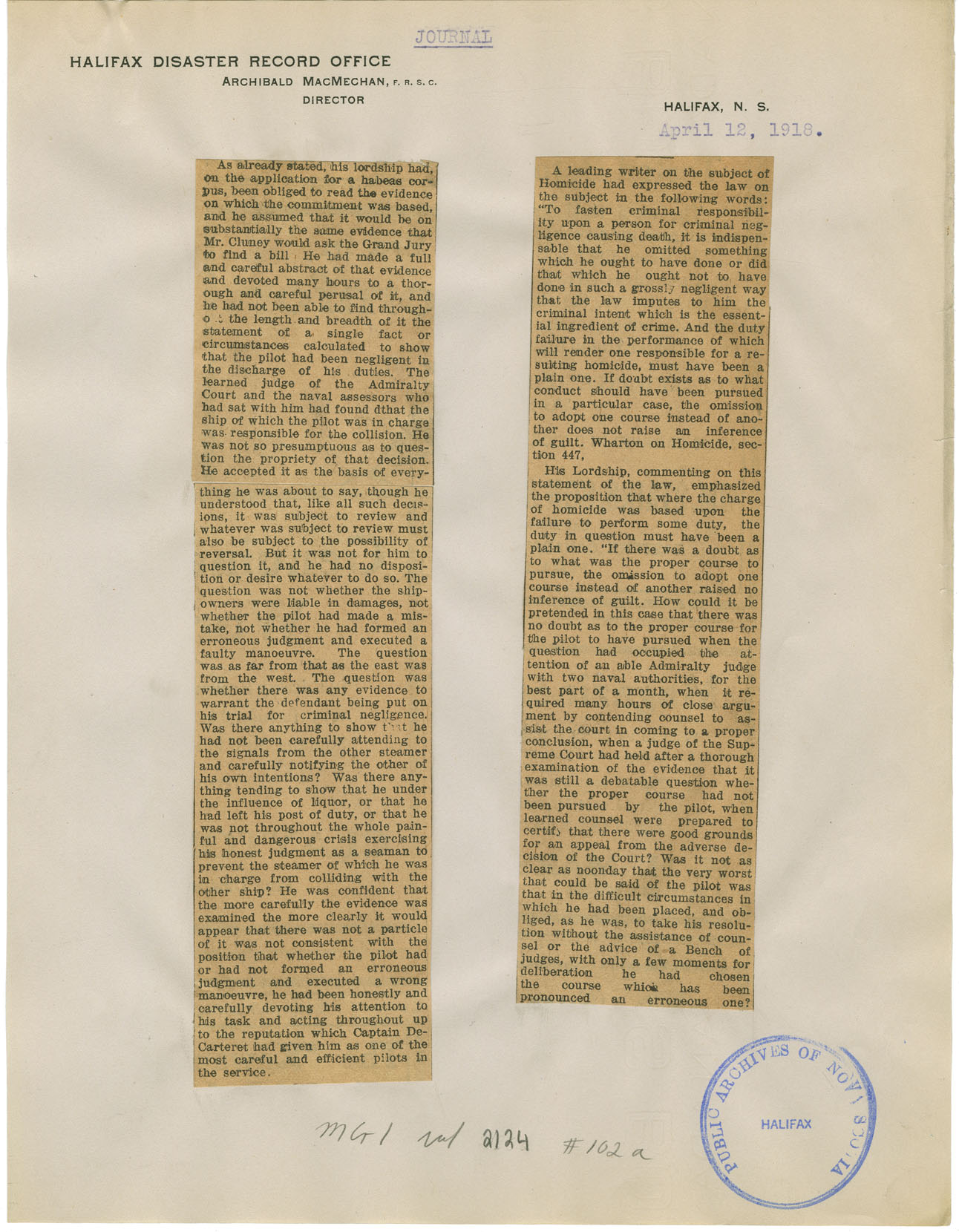

As already stated, his lordship had, on the application for a habeas corpus, been obliged to read the evidence on which the commitment was based, and he assumed that it would be on substantially the same evidence that Mr. Cluney would ask the Grand Jury to find a bill. He had made a full and careful abstract of that evidence and devoted many hours to a thorough and careful perusal of it, and he had not been able to find throughout the length and breadth of it the statement of a single fact or circumstances calculated to show that the pilot had been negligent in the discharge of his duties. The learned judge of the Admiralty Court and the naval assessors who had sat with him had found dthat the ship of which the pilot was in charge was responsible for the collision. He was not so presumptuous as to question the propriety of that decision. He accepted it as the basis of everything he was about to say, though he understood that, like all such decisions, it was subject to review and whatever was subject to review must also be subject to the possibility of reversal. But it was not for him to question it, and he had no disposition or desire whatever to do so. The question was not whether the shipowners were liable in damages, not whether the pilot made a mistake, not whether he had formed an erroneous judgement and executed a faulty manoeuvre. The question was as far from that as the east was from the west. The question was whether there was any evidence to warrant the defendant being put on his trial for criminal negligence. Was there anything to show that he had not been carefully attending to the signals from the other steamer and carefully notifying the other of his own intentions? Was there anything tending to show that he under the influence of liquor, or that he had left his post of duty, or that he was not throughout the whole painful and dangerous crisis exercising his honest judgement as a seaman to prevent the steamer of which he was in charge from colliding with that other ship? He was confident that the more carefully the evidence was examined the more clearly it would appear that there was not a particle of it was not consistent with the position that whether the pilot had or had not formed an erroneous judgement and executed a wrong manoeuvre, he had been honestly and carefully devoting his attention to his task and acting throughout up to the reputation which Captain Carteret had given him as one of the most careful and efficient pilots in the service.

A leading writer on the subject of Homicide had expressed the law on the subject in the following words: "To fasten criminal responsibility upon a person for criminal negligence causing death, it is indispensable that he omitted something which he ought to have done or did that which he ought not to have done in such a grossly negligent way that the law imputes to him the criminal intent which is the essential ingredient of crime. And the duty failure in the performance of which will render one responsible for a resulting homicide, must have been a plain one. If doubt exists as to what conduct should have been pursued in a particular case, the omission to adopt one course instead of another does not raise an inference of guilt. Wharton on Homicide, section 447,

His Lordship, commenting on this statement of the law, emphasized the proposition that where the charge of homicide was based upon the failure to perform some duty, the duty in question must have been a plain one. "If there was a doubt as to what was the proper course to pursue, the omission to adopt one course instead of another raised no inference of guilt. How could it be pretended in this case that there was no doubt as to the proper course for the pilot to have pursued when the question had occupied the attention of an able Admiralty judge with two naval authorities, for the best part of a month, when it required many hours of close argument by contending counsel to assist the court in coming to a proper conclusion, when a judge of the Supreme Court had held after a thorough examination of the evidence that it was still a debatable question whether the proper course had not been pursued by the pilot, when learned counsel were prepared to certify that there were good grounds for an appeal from the adverse decision of the Court? Was it not as clear as noonday that the very worst that could be said of the pilot was that in the difficult circumstances in which he had been placed, and obliged, as he was, to take his resolution without the assistance of Counsel or the advice of a Bench of judges, with only a few moments for deliberation he had chosen the course which has been pronounced an erroneous one?

PUBLIC ARCHIVES OF NOVA SCOTIA

HALIFAX

MG 1 volume 2124 number 102 a

Reference: Archibald MacMechan Nova Scotia Archives MG 1 volume 2124 number 102