Nova Scotia Archives

First World War Publicity Posters

Mora Dianne O'Neill is Associate Curator, Historical Prints and Drawings, for the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, where she is preparing an exhibition that will use many of these posters. Collective Remembrance: Propaganda Posters from the Great War will open there on 30 August 2014.

'Your King and Country Need You': Propaganda Posters from the First World War

On 5 August 1914, when the Governor General, Arthur, Duke of Connaught, proclaimed Canada's entry into the war against Germany, there was no television and radio was still a dream. The Canadian army consisted of a mere 3,110 troops. On 3 October 1914, 30,617 Canadian soldiers sailed for Britain, the first in a remarkable commitment from a young country.

By the war's end in 1918, a nation of 8,000,000 people had mobilized 620,000 troops; after the first enthusiastic rush, however, enlistment numbers fell. Canadians were served then by 138 daily newspapers; people were already used to handbills and newspaper advertisements, but bright and colourful posters in store windows and factories, on billboards and hoardings, had a more persuasive effect in encouraging enlistment during the four long years that followed.

Unprepared for the coming years of conflict, Canada needed to mobilize an army, persuade its citizens that support for the war was just and noble, inspire them to exercise thrift, and, as the years passed, to lend the government money to continue its efforts. As an instrument for propaganda — the organized dissemination of information to influence thought and action — brightly coloured lithographed posters proved efficient and effective.

Invented at the end of the 18th century, lithography was a cheap and efficient method of printing from a design drawn on limestone or a zinc plate with a grease pencil. Printing from multiple stones, using a different colour of ink for each, permitted the production of complex images. Large lithographed posters had been used effectively to advertise theatrical and circus events, and to promote immigration and political campaigns in Canada since the 1890s.

Printing firms, such as Rolph Clark or Stone Limited in Toronto, Howell Lithographic in Hamilton, Mortimer's in Ottawa, and Montreal Lithography, that employed artists, copywriters, plate-makers, and printers in a single company were ideally positioned to take advantage of the new call for posters in 1914. Such companies were largely responsible for poster production in Canada.

With no central government agency in charge, poster production to encourage enlistment was initially ad hoc and haphazard. Private companies, individuals, and regimental commanders authorized some; others were imported from Britain, where the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee [PRC] had supervised the enlistment campaign from the beginning.

The earliest PRC posters were little more than blown-up handbills that relied on slogans such as "Your King and Country Need You" [PRC 3] to attract attention, frequently in patriotically red and blue ink. Within weeks, however, British enlistment posters were utilizing strong graphic images as well, as in "Remember Belgium" [PRC 16], that paired a soldier with civilians fleeing a burning village.

The Central Recruiting Committee in Toronto followed this lead and issued several striking posters that were used across the country: "Your Chums are Fighting" [VB 126], designed by Charles Joseph Patterson in 1914, appealed to loyalty and masculinity, and raised the underlying spectre of shame. The basic theme of enlistment propaganda continued the following year in "Here's Your chance – It's Men We Want" [VB 127] and "Send More Men – Won't You Answer the Call" [VB 130], and the threat of public shaming became more blatant: "What will your answer be when your boy asks you – Father – What did you do to help when Britain fought for freedom in 1915?" [PRC 61] and "Be honest with yourself..." [PRC 129].

After 1916, when the Dominion government created the Poster War Service, some enlistment posters were produced in both English and French. Our collection includes only one pair of these, "We Will Uphold the Priceless Gem of Liberty / Nous defendrons le précieux jouau de la liberté" [59.4/7 and 10], featuring a young soldier in field uniform standing rigidly at attention under crossed flags and maple leaves.

A 19th century sensibility toward warfare, perhaps understandable given that many artist/designers were too old for service, informs most of the enlistment posters with their emphasis on duty, God, country, and the camaraderie of military service, rather than a realistic portrayal of what lay ahead for the recruits.

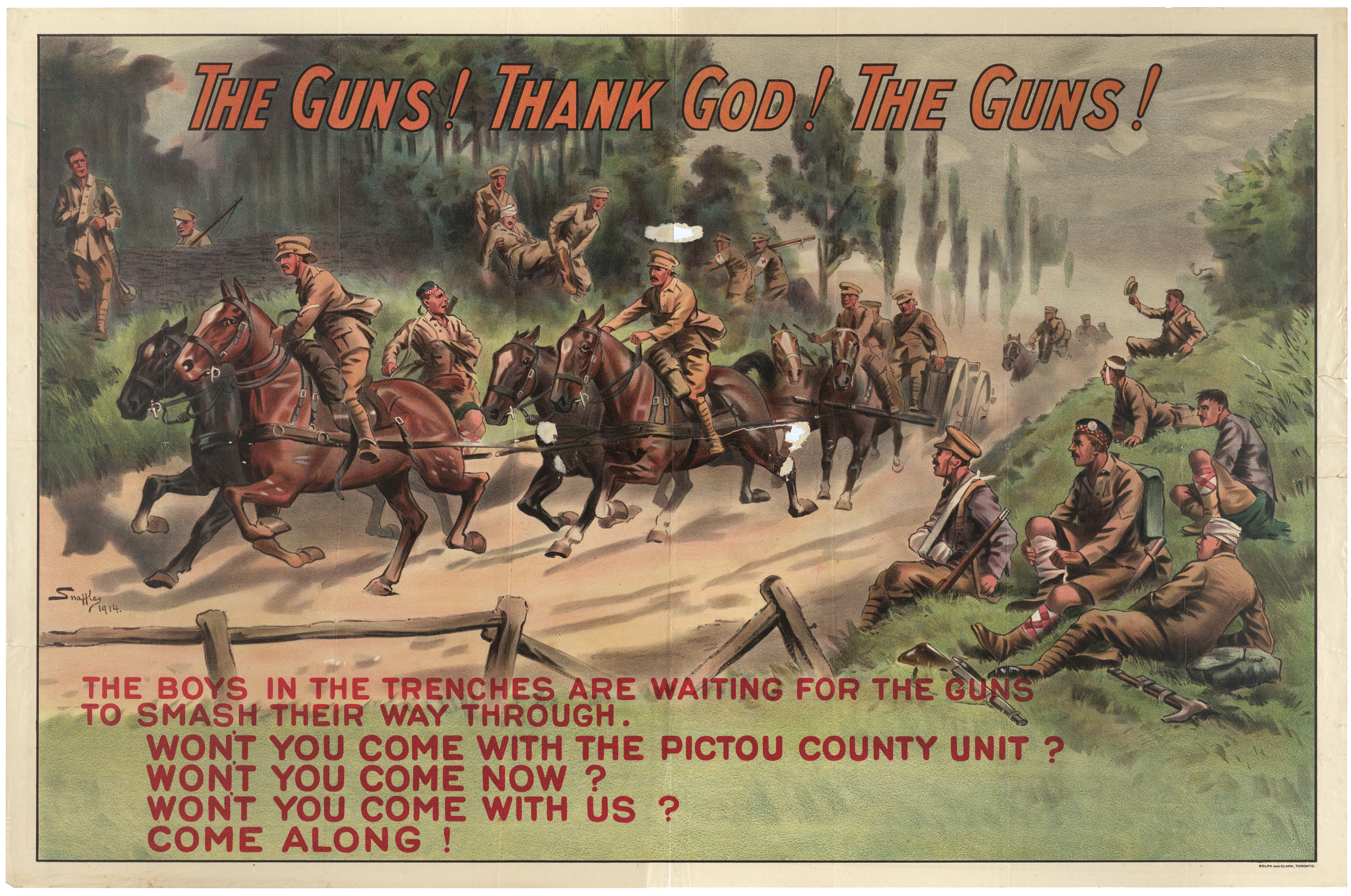

An exception is a rare recruitment poster for the Pictou County Unit [60.4/6] which employed a very realistic depiction of the front lines, based on a drawing by Charles Payne ("Snaffles"), who had sketched many scenes from the front in France during the early months of the war for The Graphic. "The guns, thank God, the guns" is a line from Rudyard Kipling's poem "Ubique," celebrating the feats of the Royal Artillery.

Probably employed in 1916 for the 22-day recruitment campaign for the 193rd Battalion of the proposed Nova Scotia Highland Brigade, only one other copy of the poster has been located in collections elsewhere. The formation of the Poster War Service probably discouraged the use of such images after it assumed supervision of enlistment posters that year, especially when casualty numbers began to climb — 75 percent of Canadian casualties date to after August 1916.

Other posters served the dual purpose of encouraging enlistment and mobilizing public support for the war effort. "Britain Needs You at Once" [PRC 108] employed the iconic image of Saint George defeating the dragon to evoke nostalgia for a better and mythic past and inspire noble sacrifice, much as "England Expects" used Admiral Nelson to recall past glory. "Keep these Flags Proudly Flying" reminded citizens that they were part of a global effort. "Take up the Sword of Justice" [PRC 111] was calculated to outrage and enflame the populace through its use of the sinking RMS Lusitania, torpedoed by a German U-boat in May 1915, and her drowning victims.

Supporting the war effort included those organizations that helped the troops, such as the Red Cross and YMCA. Although "Help the Red Cross Save Our Boys" [VB 131] suggests a Nova Scotian provenance, most Red Cross posters were imported from the United States after that country entered the war in 1917. For the most famous of these posters, Alonzo Foringer appropriated the image of Michelangelo's "Pieta." "The Greatest Mother in the World" [VB 129], which featured a monumental nurse cradling an injured soldier on a stretcher, demonstrates the effectiveness of an emotional appeal in propaganda.

Posters also called on the general public to support war industries and food production that fed the overseas army and its voracious weapons. "We're both needed to serve the Guns!" [PRC 85c] and "The Key to the Situation" [116] are both reminders that the manufacture of munitions was a large part of Canada's contribution to the war effort. "Canada's Butter Opportunity" [butter] was one of a series of posters issued by the newly-established Canada Food Board calling on farmers to increase production, and on citizens to limit their intake of such items so that more could be sent overseas.

By far the greatest number of Canadian posters, after the basic enlistment type, were those entreating the purchase of 'Victory Bonds' (originally called 'war bonds'). Canada's expenditure on the war effort had reached one million dollars a day; rather than continue to borrow from foreign banks, the government tried an approach to its own citizens.

Designed to raise $150,000,000, the first 'Victory Loan' campaign in 1917 netted instead an amazing $400,000,000. Since much of that success was attributed to positive response to the campaign poster, "If ye break faith" [VB 137], posters became an important part of each succeeding campaign.

The Victory Loan Dominion Publicity Committee organized the campaigns, whose posters employed many of the same devices to encourage contributions: slogans, suggestions of shame or self-interest, demonizing of the enemy, and appeals to loyalty, duty, and sacrifice. Slogans like "Faith in Canada" [WP 3] and "Yours not to do and die" [WP 8a] reinforced poster images. "Canada's Grain Cannot be Sold Unless you Buy Victory Bonds" [59.3/6] placed the onus on the citizen to support the campaign, but "Cash Quick" [WP 15] reminded him/her of the personal usefulness of government bonds.

Banking on the outrage aroused by the sinking on 27 June 1918 of the Red Cross Transport Landovery Castle, bound from Halifax for Liverpool, with the loss of 14 nurses and 83 other medical personnel, the Committee printed 60,000 of the "Kultur vs Humanity" [WP 2] poster to spark the sale of more Victory bonds. The German spelling of "Kultur" offered a potent reminder of the enemy.

The poster had particular relevance for Nova Scotia because one of the drowned nurses was Margaret Marjorie Fraser, whose father, Duncan C. Fraser, had served as lieutenant-governor between 1906 and 1910. Although the faces will not be recognized immediately today, everyone then would have known the Kaiser, Field-Marshal von Hindenburg, Crown Prince Wilhelm, and Admiral von Tirpitz, the "4 Reasons for Buying Victory Bonds" [59.4/8] in 1917.

The soldier seen from behind in "Back Him Up" [WP 6] added a touch of humour to the call of duty; the crowd of ordinary workers around the maple-leaf-crowned figure of Canada in "Our Export Trade is Vital" [WP 7] encouraged the same profession of loyalty in others; and "Re-Establish Him" [WP 10] reminded people that continued sacrifice was needed to re-integrate returning soldiers into society.

The passage of a century has made the era of the Great War a foreign country, but the immediacy of their images and the intensity of the feelings they still convey make these posters passports to a by-gone era in a way that words alone cannot achieve. Propaganda posters from the Great War were never intended to be archival documents and their survival is largely a function of chance — even the government in Ottawa did not instruct the Public Archives of Canada to begin saving examples of the posters until 1916.

The Nova Scotia Archives collection comes primarily from three donors. Violet Black probably acquired her collection from her father, William Marshall Black, who operated the Wolfville Opera House where posters would have been displayed. The Ronald St. John Macdonald collection was likely amassed by his father, Lieutenant-Colonel R. St. J. Macdonald, a doctor who served at the 3rd and 9th Stationary Hospitals during the war. The set of posters assembled by Martin McGrath of Toronto contains primarily those promoting Victory Bond sales after 1917, although it also includes a few of the early posters imported from Britain.

Sources

Cameron, James M. Pictonians in Arms: A Military History of Pictou County, Nova Scotia (Fredericton, ca.1969)

Choko, Marc H. Canadian War Posters (Laval, 1994)

Petz, Derek John. Past Perspectives: Posters, Modernism, and Popular Culture in England and Canada during the Great War (Honours BA, U of T, 1992)

Rickards, Maurice. Posters of the First World War (London, 1968)

Stacey, Robert H. The Canadian Poster Book: 100 Years of the Poster in Canada (Toronto, 1979)

Library and Archives Canada. Department of National Defence fonds, RG24, 'Pre-unification Army Records,' sous-fonds 'Army Historical Section,' series 'Registry Files,' sub-series vol. 1744, file 'Canadian Record and Commemoration of the War,' 1919

http:///www.gwpda.org/naval/1cdncvy.htm

Figure for first troop contingent

Dr. Serge Durflinger

Poster War Service

Poster Collection Sites: Imperial War Museum; Canadian War Museum; McMaster University; McGill University; Archives of Ontario; Library of Congress